(Advertisement)

Tube City Community Media Inc. is seeking freelance writers to help cover city council, news and feature stories in McKeesport, Duquesne, White Oak and the neighboring communities. High school and college students seeking work experience are encouraged to apply; we are willing to work with students who need credit toward class assignments. Please send cover letter, resume, two writing samples and the name of a reference (an employer, supervisor, teacher, etc. -- not a relative) to tubecitytiger@gmail.com.

Ads start at $1 per day, minimum seven days.

Remembering the Flood of '36

By Jason Togyer

The Tube City Almanac

March 22, 2016

Posted in: History

© Tube City Community Media Inc., all rights reserved

(Above: Scene in the East End of McKeesport, below Highland Grove, during the March 1936 flood.)

. . .

The winter of 1936 was like a lot of winters in Western Pennsylvania --- gloomy and cloudy, with rain and snow, alternating with snow and rain. But in mid-March, a storm center traveling south from Canada collided with another storm moving north from the Gulf of Mexico. Then two smaller storms merged into those.

And beginning March 9, 1936, and continuing for the next two weeks, parts of New England, New York and Pennsylvania were drenched with up to 12 inches of rain. It saturated the ground and filled creeks and streams. And when another storm system moved through on March 16, 1936, the water had nowhere to go.

The end result was the so-called "St. Patrick's Day Flood of 1936" --- the worst ever seen in Western Pennsylvania. More than 80 people in the Pittsburgh area died in that flood, 80 years ago this month, including a McKeesport police officer, and property damage was estimated at well over $100 million.

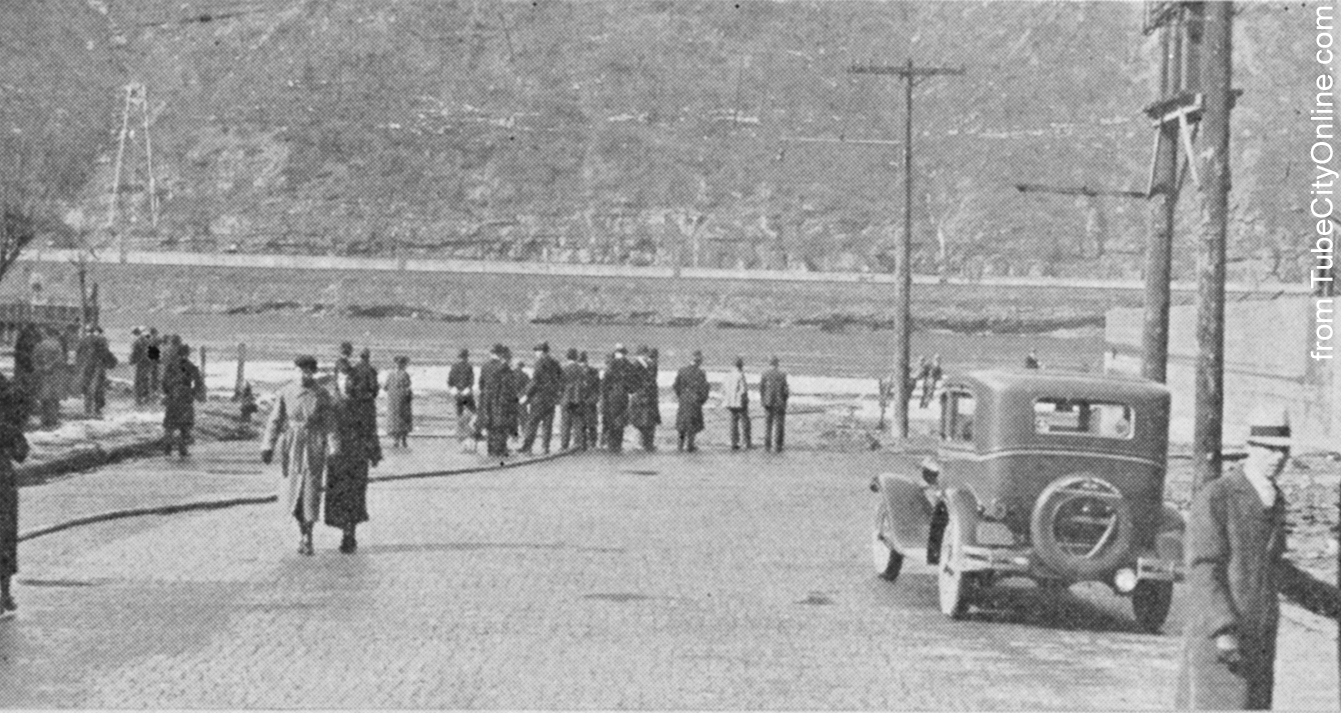

(Above: Crowd watches the Monongahela River rise at the end of Market Street. This area was redeveloped in the 1950s and is now part of U.S. Steel's idled McKeesport Tubular Operations plant.)

At the beginning of March, snow was 4 to 6 inches deep in parts of the Allegheny and Applachian mountains.

Then came the rain. On March 16 and 17 alone, more than 2 inches of rain fell in McKeesport. Clairton reported 2.5 inches and Irwin nearly 3. More than 4 inches of rain was recorded in Somerset and 2.5 inches in Connellsville.

The combination of rain and warmer-than-usual temperatures melted that snow quickly. From the hills, the rain and melted snow flowed into creeks, and then into the Allegheny, Monongahela, Kiskimenitas, Youghiogheny and Conemaugh rivers, which all ultimately drained into the Ohio.

Catastrophe followed.

(Above: Flooding along East Fifth Avenue, near the present-day on-ramps for the McKeesport-Duquesne Bridge.)

But despite the ever-present danger of flooding in Western Pennsylvania --- especially in the early spring --- everyone was slow to realize just how bad things were about to get. On March 16, the Pittsburgh Press and the Post-Gazette both predicted only "more rain and colder weather."

The newspapers were focused less on the real storm clouds over Pennsylvania than on the imagined storm clouds over Europe. Less than two weeks earlier, the German army had re-occupied the Rhineland --- an area west of the Rhine River near Belgium and the Netherlands --- in violation of the treaties that ended World War I.

Experts wondered whether another World War was imminent.

Meanwhile, on the night of March 16, the water started rising. Rivers are measured in "gage height" --- a reference to the surface level of the water compared to a fixed point on the shore.

At Charleroi, upriver from McKeesport, the gage height of the Monongahela went from 5 feet, to 14 feet a day later, then to 22 feet. And the speed of the water rapidly increased, too, to 10 or 12 times its rate in early March.

At Sutersville, the gage height of the Youghiogheny went from 7 feet to 30 feet in 48 hours. Likewise, the speed of the water increased alarmingly --- water was coming down the Yough eight or 10 times the rate a few days earlier.

. . .

(Above: The flood submerged much of the neighborhood along the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad tracks in Versailles borough.)

By the morning of March 18, most of Pittsburgh's Golden Triangle was under water estimated at 20 feet deep in some streets. The water reached the second story windows of buildings along Fifth and Liberty avenues and nearly to the bottom of the marquee on the Stanley Theater (now the Benedum Center).

A fire raged out of control at a Lawrenceville oil storage depot --- water surrounded the plant, but firefighters couldn't reach it --- while another fire killed seven people, including six children in Etna. They were "trapped between fire and flood" in their homes on that borough's Union Street, as the Post-Gazette said.

In the ultimate irony, the Pittsburgh office of what was then known as the U.S. Weather Bureau was knocked out of commission for the first time since it had been created.

Of Pittsburgh's five radio stations, only KDKA (then on 980 kHz AM) continued operating; unlike the other stations, KDKA's transmitter outside of Saxonburg had a 450-kilowatt backup power supply. The station broadcast emergency information throughout the disaster, but because most of the area had lost electricity, few people could hear the bulletins, except on battery-powered or crystal sets.

. . .

In McKeesport, 600 people were forced to flee the rising waters on March 18 --- mainly people who lived in the old "First Ward," an ethnic neighborhood where the Youghiogheny flows into the Monongahela. (The neighborhood was wiped out in the late 1950s; U.S. Steel's idled McKeesport Tubular Operations plant now occupies the land.)

But in 1936, it was a teeming ethnic neighborhood, mostly full of Eastern Europeans. At the corner of Second Avenue and Market Street, McKeesport police and firefighters were attempting to evacuate people from their homes when city police Officer Joseph Hopkins (some sources say "John") was trapped by the fast-rising water and forced to climb a telephone pole to escape.

Three times, McKeesport firefighters and police attempted to reach Hopkins using a rowboat, only to get snagged on the telephone wires that were now underwater. With the waters still rising, motorcycle police Officer John H. Sellman and firefighter John Bissell rowed out to make another attempt.

The water overturned their boat and Sellman was swept away by the fast-moving current. Hopkins and another police officer, Robert Caughlin, saved Bissell, who was knocked unconscious but survived.

Sellman's body wasn't recovered until April 21 when an employee of the Union Railroad spotted it floating in the water under the McKeesport-Duquesne Bridge. It was still clad in his police uniform.

. . .

(Above: Rescuers search the intersection of Market Street and Second Avenue near where McKeesport police officer John Sellman drowned.)

Soon, water reached nearly to the bottoms of the Jerome Avenue Bridge and the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad bridge across the Youghiogheny.

Four feet of water filled the press room of the Daily News on Walnut Street, and editors rushed to the offices of the News-Dispatch in Jeannette to put out an emergency paper.

The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad cancelled all passenger trains through McKeesport; the Pennsylvania Railroad did the same for trains through the Turtle Creek valley.

In Dravosburg, as water lapped at the windows of the First National Bank on the corner of McClure Street and River Road, officials removed $32,000 in currency and took it to an "unnamed safe place."

. . .

(Above: Flood waters along East Fifth Avenue, near the present site of the McKeesport-Duquesne Bridge off-ramps.)

Water covered Airbrake Avenue in Wilmerding and Turtle Creek, as well as Braddock Avenue in East Pittsburgh, where the flood was four feet deep.

The cold temperatures and wet conditions left many victims suffering from hypothermia and frostbite, as well as injuries caused by accidents and exposure to the deep, fast-moving water. Braddock General Hospital was filled to capacity with more 100 victims of exposure to the water and cold; two temporary hospitals were opened on the third floor of the Braddock police station and at the General Braddock Brewing Co. on Halket Avenue.

Speaking of breweries, the Duquesne Brewing Co. ran ads in local newspapers reassuring customers that its beer was boiled and "scientifically sanitary." "For your health's sake be safe," the ads said. "Drink Duquesne Beer ... our great capacity assures ample supply."

U.S. Steel closed its Homestead, Edgar Thomson and Duquesne steel mills, while Clairton Works stayed partially open --- although the steel-making portion was shut down, the coke plant continued to operate.

At night, deputy sheriffs patrolled the streets of Homestead and Munhall, looking for looters, though Homestead Burgess John J. Cavanaugh told reporters "everything is completely under control" and there was "no further cause for alarm."

In Braddock, two young men defied police orders to stay out of the fast and swollen river, and took a canoe out for a joyride on March 21. When the canoe collided with a barge and tipped over, one of them, Walter Jamkouski, 20, drowned.

. . .

(Above: McKeesporters line up for fresh drinking water.)

It took days for the water to recede. Power in McKeesport was completely out, as was telephone and telegraph service. Conditions had been reduced "almost to (a) primitive state," reported the Daily News.

Hundreds of McKeesport residents were sleeping in emergency shelters set up at the Hungarian Social Hall on Market Street and at the B'nai Brith Synagogue on Evans Avenue.

Nurses from McKeesport Hospital walked darkened streets looking for the sick and injured. Despite the loss of electricity, the hospital admitted 45 flood victims and even performed three emergency operations --- by flashlight, because candles were banned for fear of fire. Doctors also delivered six babies, four girls and two boys.

Lack of safe food and clean water was a very real concern. "The municipal water supply is all but exhausted due to an enforced shutdown of the filtration plant," the Daily News reported.

Water was brought into McKeesport by tanker truck from outlying areas, including from springs in Elizabeth Twp. that were untouched by flood water.

A fleet of seven Allegheny County tanker trucks was kept busy hauling fresh water from a spring near South Park into Braddock, Duquesne, Munhall and Swissvale. Boy Scouts, police and volunteers helped distribute clean drinking water to homes in Homestead.

. . .

(Above: Wrecked building deposited on the river bank near the present site of McKee's Point Marina.)

When the rivers and creeks returned to their banks, they left behind foul-smelling muck, and public health officials warned of the danger of typhoid fever --- an infection spread by bacteria from sewage.

McKeesport Hospital distributed typhoid vaccines and all city police and firefighters received the vaccinations. City officials urged residents not to use water from underground cisterns, and to boil any tap water for at least 20 minutes before using it.

By March 25, McKeesport City Chemist Edward Trax was able to report that the filtration plant was operating "as usual" and that city water was "safer than that obtained from nearby springs and wells."

. . .

As the water went down, the true extent of the damage also became clear. Roads were washed out or covered in mud so deep that snowplows were needed to remove it. Across Allegheny County, hundreds of bridges were closed until they could be inspected for damage.

McKeesport Mayor George Lysle estimated damage in the city alone at $500,000, or more than $8.5 million in 2016 dollars. Some 2,000 homes in the McKeesport area had been damaged, and in a few neighborhoods, crews went from door to door, pumping out basements. After the water was removed, houses were sprayed with coal tar to kill bacteria.

In an effort to prevent the spread of infectious diseases, truckloads of chloride of lime --- another disinfectant --- were hauled into Mon Valley towns to kill germs in the muck and mud left behind. Although many people fell ill from exposure, exhaustion or lack of food, no cases of typhoid were reported.

The federal government sent some 600 people from the Works Progress Administration to help with the initial clean-up in the McKeesport area; another 4,000 WPA workers would eventually pour into the Mon-Yough valley.

. . .

(Above: A Pittsburgh Press cartoon by Ralph Reichhold urges the federal government to finally start work on flood control projects)

There was another scare on March 24 when the rivers again began to rise; although low-lying parts of the McKeesport area were flooded again, the heaviest damage had already been inflicted, and the second flood was more of a nuisance than a disaster.

In all, 12 states from New England to Georgia experienced damage from the "Flood of '36," but Pennsylvania was the hardest hit, with 300,000 people left temporarily homeless and more than 100 dead. State officials estimated the property damage across Pennsylvania at $212.5 million.

At the time of the flood, the U.S. Congress had been debating for more than a year the need for new flood control measures in Pittsburgh, including nine new flood control reservoirs.

Although the U.S. House of Representatives had authorized the project, the Senate delayed, and no money was actually appropriated until 1937, after another major flood devastated Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Kentucky.

That 1937 flood --- the so-called "Super Flood" that began in late January, destroying $500 million in property and claiming nearly 400 lives --- finally spurred Congress into action. Major federal flood control legislation was passed in 1937, 1938 and 1939.

. . .

(Above: Partial map of flood control reservoirs in the Pittsburgh area. Click for full-size map. Detail from map by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Pittsburgh District)

In the Pittsburgh area, work soon began on 16 flood-control reservoirs, including the 16-mile-long Youghiogheny River Lake, which was begun in 1940 and completed in 1943.

Some of the projects would prove controversial --- especially the Allegheny Reservoir in northern Pennsylvania, which destroyed 10,000 acres of the Allegheny Reservation of the Seneca Indians, or about one-third of the land that had been promised to them in a 1794 treaty.

And the Mon Valley has continued to experience significant floods, such as the flood of Jan. 20-21, 1996.

The 1996 flood put most of Elizabeth Borough under water, closed Glenn Avenue in Port Vue and Route 136 in Bunola, Forward Twp., and caused severe damage to Sandcastle Waterpark in West Homestead. It also forced the evacuation of 450 residents of Harrison Village in McKeesport, and flooded the intersection of Eden Park Boulevard and Walnut Street in the 11th Ward.

But since flood control measures began in the 1930s, none of the floods to hit the Pittsburgh area have yet topped the biggest of them all --- the legendary St. Patrick's Day Flood, 80 years ago this month.

. . .

Sources:

Grover, Nathan C. and Lichtblau, Stephen, editors, The Floods of March 1936, Part 3: Potomac, James, and Upper Ohio Rivers (1937)

Lucas, Donald J., et al, Cornerstone of a Community: McKeesport Hospital, One Hundred Years of Caring (McKeesport Hospital, 1994)

Smith, Roland M., "The Politics of Pittsburgh Flood Control, 1936-1960," Pennsylvania History, 42 (1975)

-----, "The Flood of 1936," National Weather Service website at www.erh.noaa.gov/nerfc/historical/mar1936.htm

Jeannette News-Dispatch

-----, Photo Story of the Greatest Flood in the Century, March 17-19, 1936, Pittsburgh Section (Harry H. Hamm Co., 1936)

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

The Pittsburgh Press

The Washington (Pa.) Reporter

Originally published March 22, 2016.

In other news:

"Police Log: March 21,…" || "Retired Trooper Indic…"

TM

TM