(Advertisement)

Tube City Community Media Inc. is seeking freelance writers to help cover city council, news and feature stories in McKeesport, Duquesne, White Oak and the neighboring communities. High school and college students seeking work experience are encouraged to apply; we are willing to work with students who need credit toward class assignments. Please send cover letter, resume, two writing samples and the name of a reference (an employer, supervisor, teacher, etc. -- not a relative) to tubecitytiger@gmail.com.

Ads start at $1 per day, minimum seven days.

150 Years Ago Today: Four Local Soldiers Carried Lincoln's Body From Ford's Theater

By Jason Togyer

The Tube City Almanac

April 14, 2015

Posted in: History

Please credit © Tube City Community Media Inc., all rights reserved.

(Above: "The Assassination of President Lincoln," a Currier and Ives illustration. Library of Congress collection.)

. . .

The bloody "War Between the States" had finally ended with the surrender of Confederate forces at Appomattox, Va., on April 9, 1865.

Less than a week later, four young soldiers from the McKeesport area, stationed at Camp Barry, on the outskirts of Washington, D.C., had Friday night off --- it was Easter weekend, after all --- and decided to take in a play at Ford's Theater.

They were looking forward to a peaceful, light-hearted evening on April 14, 1865. They wouldn't have one. Instead, they would be eyewitnesses to history, 150 years ago tonight.

The four men --- Private Jabez Griffiths, 19, of McKeesport; Private Jacob Soles, 19, and Private John Corey, age unknown, both of North Versailles Twp.; and Private William Sample, about 29, address unknown --- were seated about 15 feet from President Lincoln when he was shot. They carried the stricken president out of Ford's Theater.

. . .

As the old joke goes, "Other than that, did they enjoy the play?"

Probably. "Our American Cousin" was the story of a country bumpkin from the United States who travels to England to collect his family's inheritance. It wasn't subtle --- most of the humor derived from stereotypes and puns --- but it was very, very popular. (Think of it as the Will Ferrell movie of the 1860s.)

The four men were members of Independent Battery C of the Pennsylvania Volunteer Light Infantry, assigned to help protect Washington, D.C, from invasion or attack. Camp Barry was east of the U.S. Capitol, along the Anacosta River near Benning Road.

Griffiths, though only 19, had already served two tours in the Union Army. At age 16, he had run away from home and enlisted in the 123rd Pennsylvania Infantry. Honorably discharged two years later, he re-enlisted in the Volunteer Light Infantry.

Corey had also served a previous stint in the Union Army, in the 136th Pennsylvania Infantry, before re-enlisting.

. . .

(Above: Camp Barry, Washington, D.C. Photo from the Library of Congress collection.)

It would have taken them about a hour to walk from Camp Barry to Ford's Theater. As Soles later remembered, they left the barracks late and the play had already begun when they arrived at the theater.

President Lincoln, the first lady, and Army Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancee were seated in what we would now call a "VIP" box near the stage.

The four men from the Mon Valley would have to be on their best behavior --- they were seated in the first balcony, near their commander-in-chief.

By the third act, the audience's attention was riveted to the stage. Unbeknownst to the president and his party, the door to Lincoln's box had been left unguarded. His bodyguard, a Washington, D.C., police officer who had been disciplined for sleeping and drinking on duty, had left the theater during an intermission to go to a local saloon.

But after all, the war was over. Washington was in a festive mood. The danger to Lincoln had surely passed. And besides, who would attempt to harm the president with the audience full of soldiers?

. . .

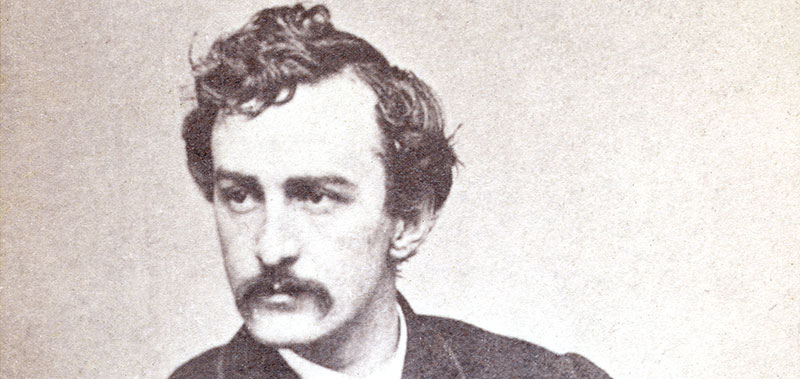

(Above: John Wilkes Booth. Photo from the Library of Congress collection.)

In the darkness outside the door to the president's box waited John Wilkes Booth, an actor and Confederate sympathizer whose family had owned slaves on their Maryland plantation. During the war, he used his status as a minor celebrity to work as a secret agent for the Confederate States of America, and helped smuggle material and information behind Union lines.

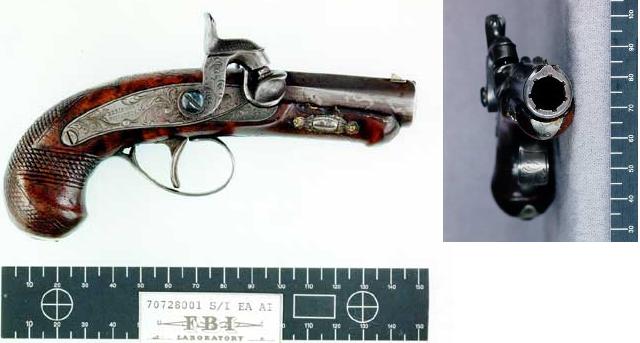

Booth considered Lincoln a "disgrace" and a tyrant, and during the war, he had unsuccessfully tried to kidnap the president. Now, as Booth crouched in the shadows, his sweaty hand clutched a single-shot Deringer pistol.

Although Booth had never performed in "Our American Cousin," he had memorized the play, and he knew that the biggest punchline was coming up in the second scene of the third act.

. . .

The second scene began. The star, actor Harry Hawk, playing the country bumpkin, had an argument with the aristocratic "Mrs. Mountchessington."

As she left the stage, Hawk shouted after her, "I don't know the manners of good society, eh? Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal --- you sockdologizing old man-trap!"

The audience roared with laughter, including Lincoln, who was well known for his sense of humor.

. . .

(Above: The pistol Booth used to kill President Lincoln. FBI photo.)

At that moment, Booth opened the door to the president's box and shot Lincoln at point-blank range, just under his left ear. Lincoln slumped forward, then jerked back.

"Mrs. Lincoln, I think it was, was the first to scream, 'The president is shot!'" Soles told the Washington (D.C.) Daily News in 1933. "We were at Lincoln's side in a second."

Rathbone, sitting with Lincoln, leaped forward and tried to grab Booth. Booth pulled a knife, stabbed the major in the arm --- slicing it open all the way down to the bone --- and then jumped from the box to the stage, fleeing the theater in the confusion.

The cry went up for a doctor. Army surgeon Charles Leale was in the audience. He pushed his way through the crowd to Lincoln's side. Two other doctors soon joined him.

. . .

There were no ambulances in those days, and precious few hospitals. Together, the medics concluded that Lincoln would not survive a bumpy, 15-minute carriage ride to the White House for examination.

Leale and the other doctors recruited the four young men from the Mon Valley to carry Lincoln out of the theater.

"We four fellows carried him to the stairway in the theater ... with his feet foremost," Soles remembered in 1931. "I was down at his feet with one of the fellows ... we had him out on the street about five minutes until we found a place to put him."

There was a boarding house across the street, run by a William Petersen. As word spread through the neighborhood of the president's shooting, a tenant of the boarding house came outside, holding a lantern. "Bring him in here! Bring him in here!"

. . .

Lincoln "felt limp, as if all the fight had gone out of him," Soles remembered. "Guards cleared the aisles and we walked to the door, and then directly across the street --- the six of us carrying him as gently as we could.

"We carried him across the street and up the steps of the house. Someone directed us to a room, where we put Lincoln into a bed."

Although official accounts say that Lincoln never regained consciousness after being shot, Soles claimed that the president spoke in a whisper to the soldiers, "Where are they taking me?"

. . .

The doctors quickly concluded that there was nothing that the medical methods of 1865 could do to save Lincoln's life. The president slipped into a coma and died about nine hours later.

"We waited around until the doctors came out and said it was fatal, and then we pulled for camp," Soles said.

Griffiths, Sample, Corey and Soles were honorably discharged on June 30, 1865, and returned to the McKeesport area, and civilian life.

. . .

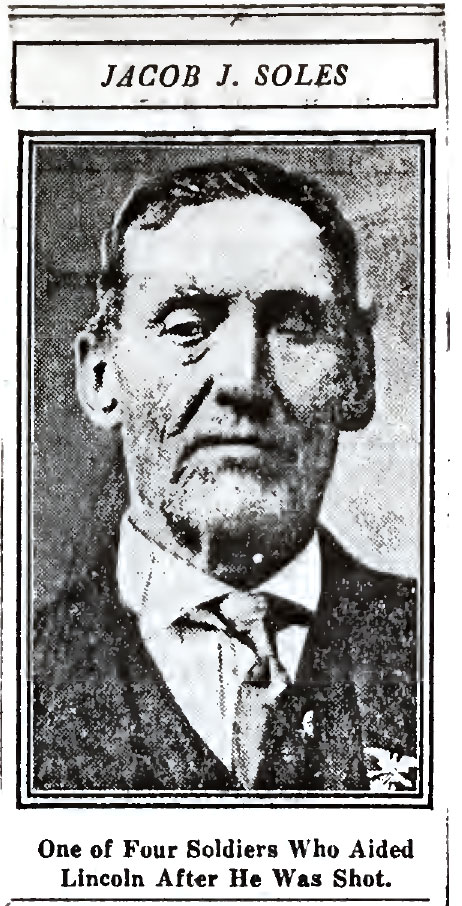

The men were forgotten for more than 60 years until an attorney and amateur historian from Uniontown, Earl T. Chamberlin, finally unearthed their names in 1931.

"It was through a friend of mine, who casually mentioned the fact that his father had known a man who helped carry Lincoln from Ford's theater, that I first learned about their story," he recalled.

Only Soles was still alive. Chamberlin interviewed Soles --- found him credible --- and tracked down Griffiths' widow in Beaver County. Then he wrote about their story in an article for the New York Times.

. . .

Soles was retired from working in a coal mine, where he had lost an eye in an accident. His buddies from Battery C were not that fortunate.

Corey died March 17, 1884. He was working on a coal barge on the Monongahela River when he fell into the water and drowned, leaving a wife and five children.

Griffiths was a celebrated riverboat captain, plying the Monongahela and Ohio rivers as far as Louisville, Ky., until he became ill with cancer in 1897. He died at age 53 the family home on Penny Street in McKeesport on Jan. 18, 1898, leaving a wife and five children, and is buried at Richland Cemetery in Dravosburg, overlooking the river he loved.

(The Dravosburg Community Archives is currently working on a history of Richland Cemetery and the people who are buried there, and Griffiths' story will be among those told.)

Sample died only five weeks after Griffiths. After the war, he was employed in a steel mill in McKeesport --- presumably National Tube Works --- until he was badly burned in an accident. He died in McKeesport Hospital on Feb. 25, 1898, age 52.

. . .

With the publication of Chamberlin's article in the Times, Soles became a minor celebrity. In his remaining years, he enjoyed sitting on the porch of his North Versailles home and regaling visitors --- including three-time Pulitzer Prize winning poet and author Carl Sandburg, who wrote an authoritative biography of Lincoln --- with the story of what happened that night in Ford's Theater.

In 2009, Soles' grandson remembered veterans' groups passing by the house during holidays to salute and honor Soles for his service in the president's final hours.

Jacob Soles died peacefully in 1936 and is buried in Monongahela Cemetery in North Braddock.

. . .

Sources:

- Author unknown, "The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln," Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection

- Obituary, Captain Jabez Griffiths, McKeesport (Pa.) Daily News, Jan. 18, 1898

- Bauder, Bob, "Local man recalls grandfather's connection to President Lincoln," Ellwood City (Pa.) Ledger, Feb. 11, 2009

- Chamberlin, Earl T., "Four Men Who Bore Lincoln from Ford's Theatre Named," The New York Times, Feb. 8, 1931

- Ibid, letter to Howard K. Terry, June 17, 1931, unpublished.

- Kalamas, Mary Ellen, "The Men Who Carried President Abraham Lincoln from Ford's Theater After He Was Shot," the Downriver Seeker, Lincoln Park, Mich., February 1985

Originally published April 14, 2015.

In other news:

"Westmoreland Official…" || "To Our Readers"

TM

TM